It’s the end of a sunny and warm December morning. Behind me is the crowded Martyrs’ square buzzing with street vendors, and in front of me is the famous Ketchaoua mosque with its outstanding fusion of Moorish and Byzantine architecture.

I’m standing in the middle of the street, with an almost empty handbag, listening to the call to prayer echoing from the surrounding mosques and watching worshipers flocking the Ketchaoua doors.

I can feel people looking at me strangely. It’s clear I’m not from the area and they are probably wondering why I’m standing here, at the foot of the Casbah of Algiers, with one leg to the front and another to the back.

It’s been over 10 years since I last set foot here. At the time, I visited the Casbah with my parents as it wasn’t considered safe to go there alone, but today I want to explore it by myself. I want to see what has become of this old quarter of the city.

The Casbah of Algiers is the oldest quarter of the city, nestled on top of a hill with white washed houses overlooking the Mediterranean sea. It has been an unsafe quarter for tourists and locals alike for decades during the civil unrest in Algeria – pretty much like the rest of the country, but has recently started reshaping itself with various renovation projects and guided tours.

El-Casbah, as the locals call it, is full of historical and religious sights. A walk through it feels like a journey in the past. It’s been inhabited since at least the 6th century BC by the Phoenicians and has been the heart of the capital since the Ottoman era as seen from the plethora of palaces and mosques scattered across its alleyways. During the Algerian revolution against the French occupation, it played an essential role as a base for planning and hiding.

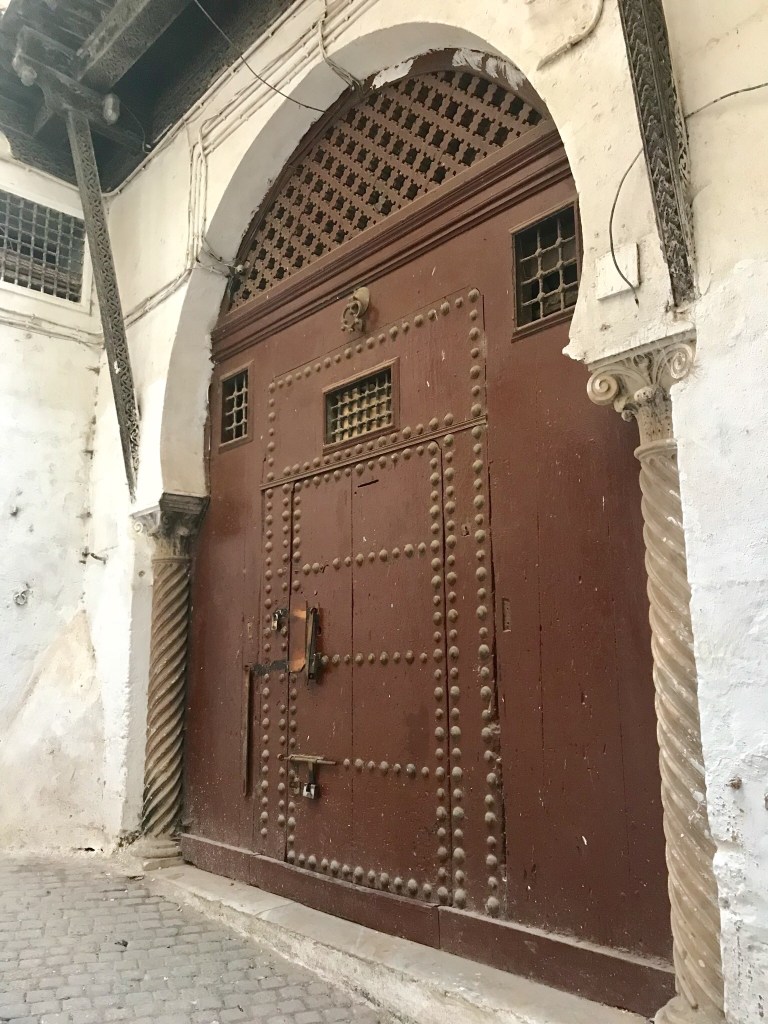

I start my walk in the lower part of the Casbah, which has a number of ancient Ottoman palaces like Dar Aziza and Dar Hassan Pacha – all within a short walking distance from each other. They were built in the 16th and 18th centuries by the Deys and Pachas of Algiers, and have very similar moorish architecture, which dominated the region at the time.

In the centre of each palace is a marble courtyard with a fountain in the middle to keep the house cool during the hot summer days. The rooms are split across two floors surrounding the courtyard, and the walls are decorated with different types and colours of faience that give each palace a unique style.

Dar Mustapha Pacha alone is covered with more than 500000 Italian and Dutch faience mostly coming from Delft in the Netherlands. Dar Khedaoudj el-Amia, which was originally the palace of Ahmed Rais then the home of Hassan’s Pacha daughter, is now home to the national museum of arts and popular traditions.

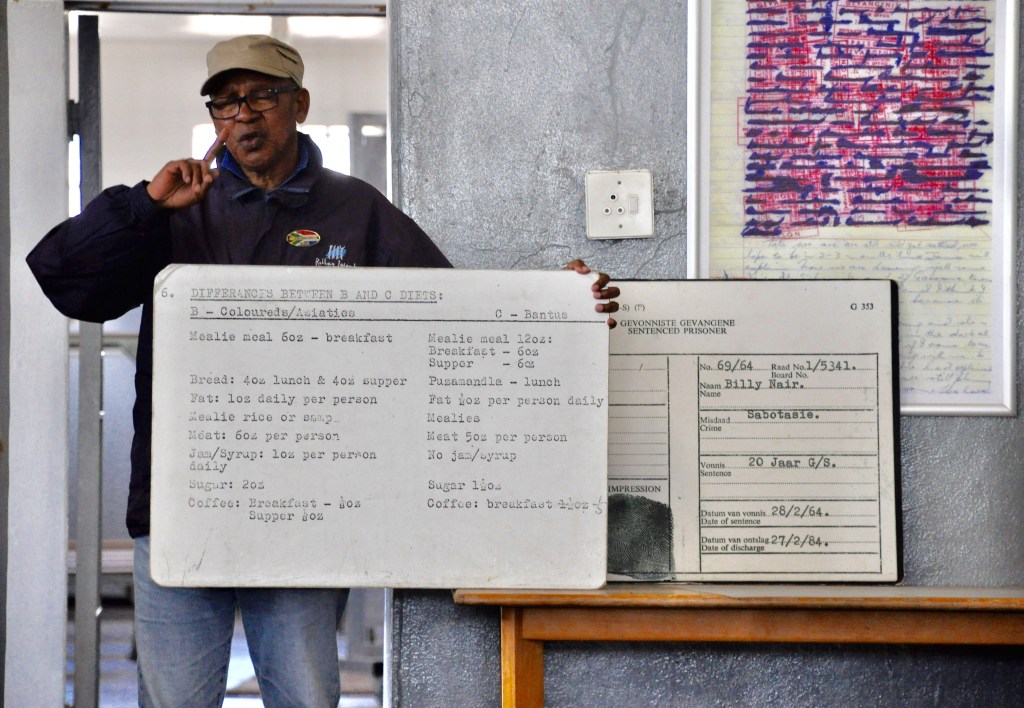

As I was admiring the grandeur and style of a wooden door in one of the alleyways, I suddenly hear someone asking me “Do you know why the knock handle is so high up?”. “No” I reply. So, he continues “during the Ottoman era, the nobles used horses to go around. So, to avoid getting off their horses to knock on doors, they placed the knock handles high. You can also see that there is a large and a small door – the large one is for people coming on horses”.

The man then walks few steps towards the end of the alleyway and points at a sign with two hands carved in the top corner of the wall explaining that it was used to mark the streets inhabited by Muslims. It’s amazing how people here are very eager to share information about the history of the place, their struggles and the way they live.

From the Ottoman era, I move to a more recent period of the Algerian history. I’m now in front of the museum of Ali la Pointe, located in the middle part of the Casbah, which was the house where four famous freedom fighters got blown up during a raid of the French military, as they refused to surrender.

The alleyway leading to the museum is decorated with colourful street art and Algerian flags including a painting of the four martyrs. As I look around, I get flashbacks from the famous Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 black and white movie – the Battle of Algiers, which was shot here and is a true recreation of the Algerian uprising against the French occupation.

My next stop is Sidi Abdarrahmane mausoleum, which is a mosque, a mausoleum and a graveyard where some very notable people have been buried including patron saint Sidi Abdarrahmane. It was built in 1696, and today it’s a place of worship and spiritual connection. The view from here is breathtaking with the mausoleum’s white dome and minaret, emerging from behind the trees, overlooking the blue sea and clear skies.

It’s now mid-afternoon. The streets are not very busy in this part of the Casbah, apart from the men sitting by their front doors watching passersby, kids playing football in a courtyard and a group of men playing dominoes.

The afternoon here seems to be long and enjoyable. Someone once told me “In Europe, you have watches, in Africa we have time”, and he couldn’t be more right as you can clearly see people here enjoying the slow movement of the day.

I continue to walk up the alleyways until I reach the Palace of the Dey at the top of the Casbah, which was completed in 1596 and was once the second largest palace in the Ottoman Empire. During the French occupation, it served as a military base for the French army. As much as I want to spend more time strolling through the alleyways of the upper Casbah, I need to head down to Bastion 23 (Palais des Rais) before it closes.

Bastion 23 is a magnificent historical monument with three palaces and five fishermen houses, built in 1576 by the famous corsair Barbarosse. A walk around it gives an evocative insight into how the Deys and corsairs lived during the Ottoman era.

“If it wasn’t for a group of people who sponsored its renovation, this palace wouldn’t exist today” tells me one of the guards. The monument is indeed well refurbished compared to the other palaces and certainly the alleyways I walked through earlier today.

As I step into the terrace overlooking the blue sea, I see the canons surrounding its walls and start to picture how this place looked back in the 17th and 18th centuries when Algeria had one of the most powerful and feared fleets in the Mediterranean.

As I leave the Casbah behind me and start walking along the bay, I suddenly wake up to the sight of a beautiful sunset settling down in the horizon. I stare in awe and wonder if this place will ever be buzzing with tourists, or will it continue to be a destination for the daring ones who want to travel through its memory lanes and enjoy its unspoilt beauty.

Or, will it be for people like me who want to explore the homeland they once left behind. After all, this trip may not have been to satisfy my curiosity of what had become of a place I visited a long time ago but most probably to settle the feelings of nostalgia from self exile.