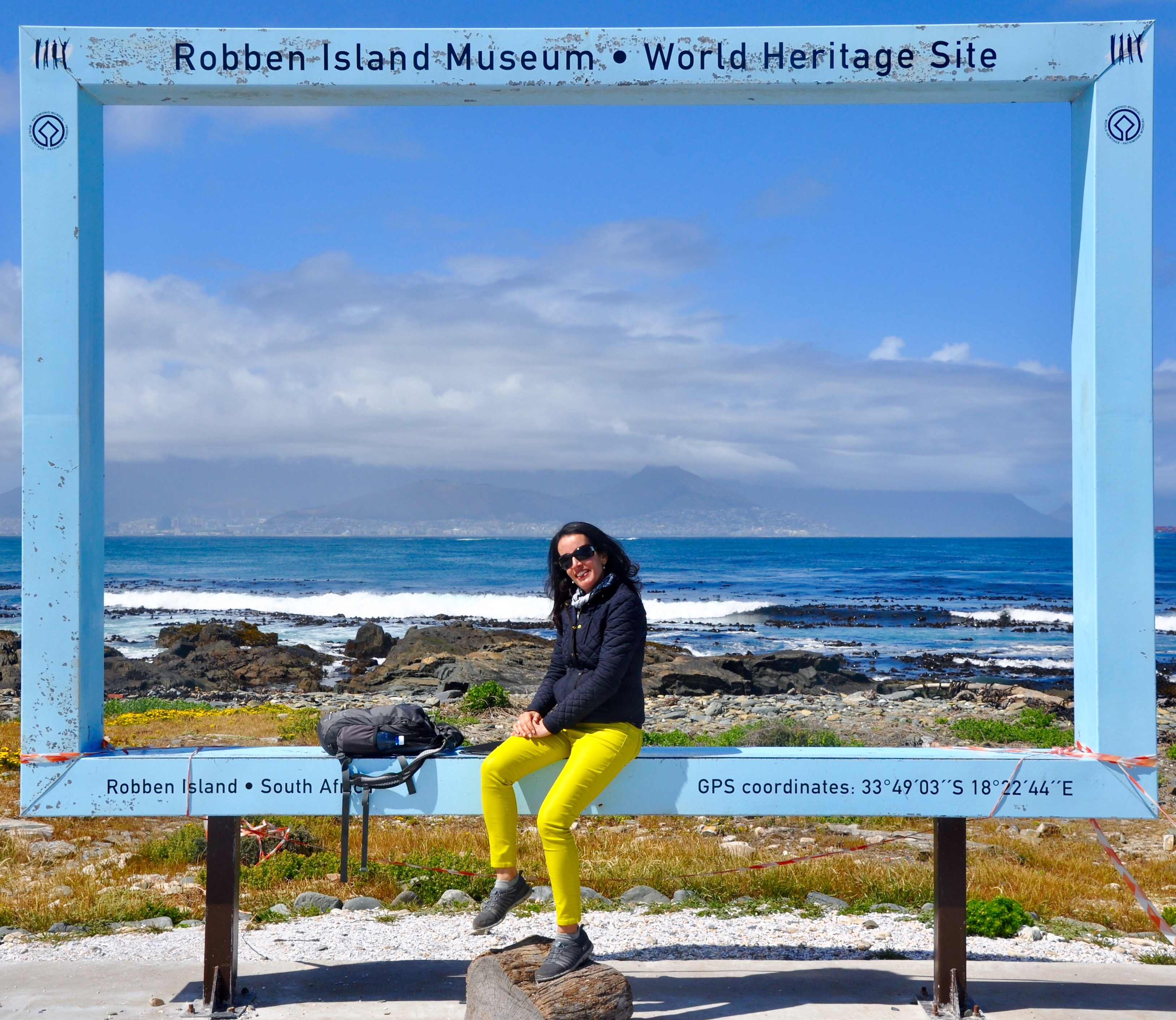

It’s just after 9am as we leave the busy V&A Waterfront behind us and head towards Robben Island – an island unlike others that is famous not for its turquoise blue waters and expensive hotel chains, but for its role in reshaping South Africa’s political history and the struggle against apartheid.

Robben Island has been a place of imprisonment and isolation for centuries starting from the time when the Dutch arrived in the 17th-century to when the British took control. In the second half of the 19th-century, it became a leper colony before turning into a military base during World War II and then a maximum security prison during the apartheid regime in the 20th-century.

Today, it’s an island with a very small population that includes tour guides and their families. It opens its doors to tourists who want to learn about the struggle against apartheid and see the place where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for 18 years before becoming the first black and democratically elected president in South Africa.

To many in South Africa and abroad, Robben Island is a symbol of forgiveness, triumph over adversity and most importantly freedom. As Ahmed Kathrada (prisoner 468/64 1964-1982) put it “We want Robben Island to reflect the triumph of freedom and human dignity over oppression and humiliation.”

As we arrive to the island, we are welcomed by clear blue skies and the sound of screaming seagulls guarding its shoreline. We are then escorted to board buses, which once used to transport prisoners, and today serve as the island’s tour buses. Our bus; number 2, we are asked to remember so we know which one to board at the different tour stops, is guided by a former political prisoner who returned to work in the island years after being released.

Our first stop is the limestone quarry, where prisoners were forced to work and dig up stones for years. It’s around 11am now; the sun is high in the sky and scorching hot – a perfect setting to picture part of the struggle the prisoners lived when breaking stones under the burning sun. In the middle of the quarry lies the cairn of stones laid by Nelson Mandela and former prisoners on their first reunion in the island in 1995, as a memorial to their hard work and daily life back then.

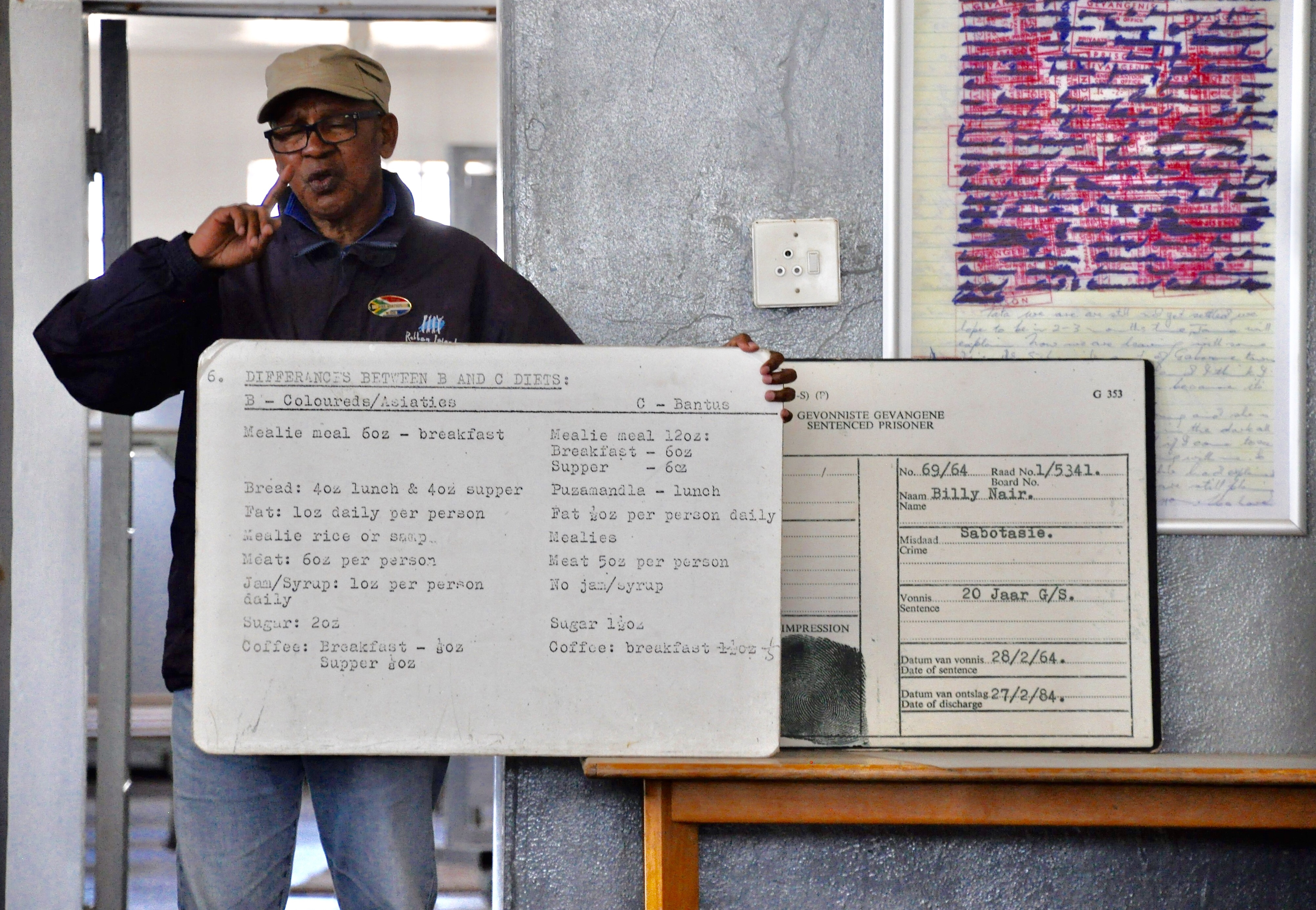

After a short stop at the military bunker, we board our buses again towards the maximum security prison. As we arrive, we are greeted by a new guide who takes us on a tour around the different sections of the prison he once was a prisoner in. The prison was split into 4 sections: A, B, C and D. Each section was dedicated to different groups of prisoners based on their race and sentence.

The tour around the prison is probably the most emotional and distressing one. As we start our walk in a long dark corridor and listen to the stories from our guide, it’s easy to picture the suffering of the political prisoners back then.

The cells on either side of the corridor have cemented floors, a tiny window; covered with iron bars, and two doors: a metal one with bars on the inside and a thick brown wooden door on the outside. They are all very small; as Mandela put it in his Long Walk to Freedom “I could walk the length of my cell in three paces. When I lay down, I could feel the wall with my feet and my head grazed the concrete at the other side.”

“This is Mandela’s cell”, our guide tells us, so we all queue eagerly to take a peek through the closed iron door. It looks the same as all the other cells. On the floor is a straw mat he used to sleep on, a small side table; with a metal cup, a plate and a spoon, and an iron sanitary bucket.

Our guide Sama seems open to answer any questions we have, but I’m finding it hard to ask about the past, especially after walking around the cells and seeing what had become of these former prisoners. Their faces still bear the scars of past struggles, their bodies are frail and their eyes are weak from all the hard work and sharp light in the quarry.

“Even diet was discriminatory and was subject to apartheid regulation” Sama tells us holding a board with the breakfast menu, which was split into 2 sections: group B for the coloured (mixed race) and Asian prisoners, and group C for Bantus (Black Africans). The latter had smaller sizes and less content. “We were told that our bodies don’t need sugar and require small portions only since we were thin” Sama continues with a smirk in his face.

After completing the tour in the inside of the prison, we step into the courtyard, which has a small garden on the side. “This is where Nelson Mandela used to grow tomatoes” Sama tells us. “He also used to hide his journals, which later turned into A Long Walk to Freedom, under the soil”, he continues.

It’s almost 1pm, the tour has ended and we are rushed back to the ferry terminal, after passing by the souvenir shop where I grabbed a couple of books: “A Long Walk to Freedom” by Nelson Mandela and “Robert Sobukwe how can man die better” by Benjamin Pogrund. “Robert Sobukwe was a very important icon in the struggle against apartheid. He’s not very famous like Mandela, but his work was equally important” the guide tells me – I cannot wait to read the book.

The entire trip has been emotionally challenging but equally inspiring to see how these ex-political prisoners turned a big tragedy that took their youthful years into something positive. They used their years in prison to educate themselves and plan for a better future despite the harsh conditions. Today, they continue to educate visitors about the meaning of freedom, forgiveness and perseverance.

It’s certainly not easy to go back and work in a place where one was humiliated for years. One needs a big heart and a wise soul to take that step. This is not just about Nelson Mandela who changed the face of South Africa, but it’s also about all former political prisoners who still live there and use that experience to educate the world.