The day I told people I was going to the West Bank, I got incredulous looks and moments of silence before I heard someone saying “Wow! Interesting choice of destination! Are you sure it’s safe to go there?”.

In reality, I was also skeptical. What’s meant to be a land of spirituality, holiness and historical richness has been in the midst of the biggest political crisis and under occupation for decades.

However, once you set foot there, it’s a different story. You will find it hard not to be moved by the myriad of beautiful landscapes, the spiritual magnetism of the place and the generosity of the Palestinians.

If the West Bank hasn’t made it to your travel bucket list yet, here are ten reasons why it should whether you are looking for a spiritual journey or an adventure to satisfy your curiosity.

1. The Old City of Jerusalem: A historical journey inside its walls

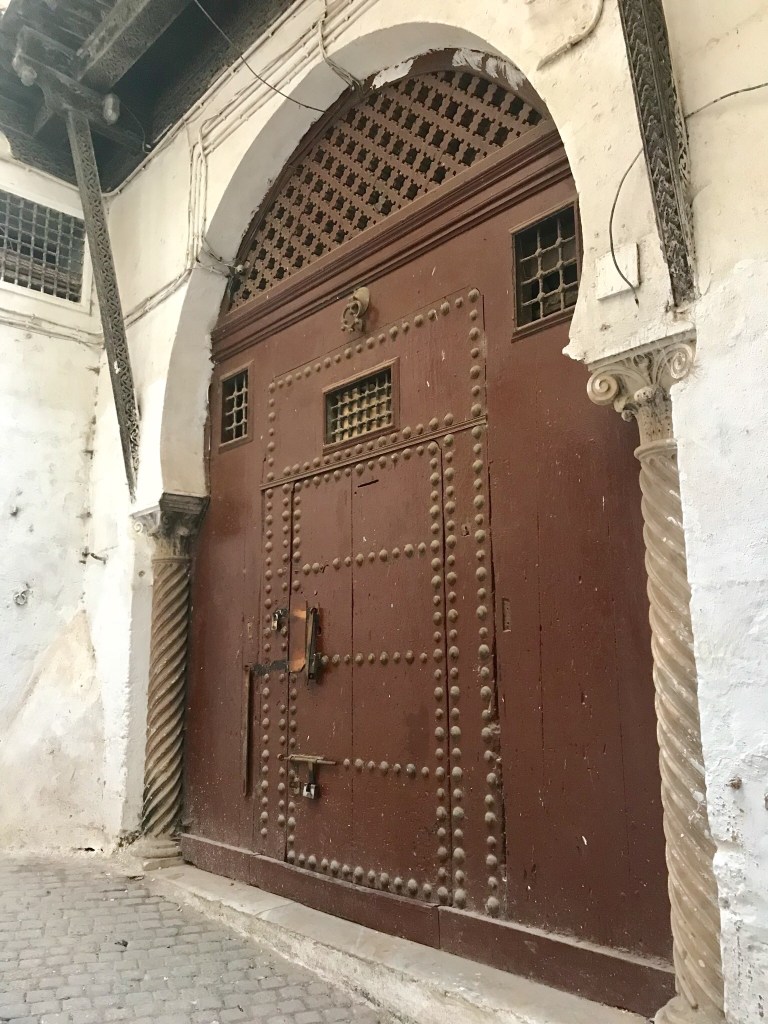

As you step inside the 16th-century Ottoman wall surrounding the Old City of Jerusalem, you get transported back into the pages of history, where past civilisations lived and layers of ancient architecture and monuments still stand.

The Old City is a labyrinth of small alleyways filled with traditional souks and colourful merchandise. It’s divided into four quarters: Armenian, Christian, Jewish and Muslim – each with its own style.

The Muslim quarter is the most vibrant with its small eateries and street markets. Like its neighbouring Armenian and Christian quarters, it has preserved its traditional character. The Jewish quarter, on the other hand, has lost its historical style to a modern look.

2. Jerusalem: Home to some of the holiest sites in the world

Most people visit Jerusalem for spiritual reasons, and the ones who don’t can still sense its spiritual magnetism through its religious sites and devoted pilgrims. The Old City of Jerusalem is home to a plethora of religious sites that are of great significance to the three Abrahamic faiths.

Whether you’re visiting for religious reasons or not, it’s hard not to be moved by the sight of Muslim worshipers flocking the doors of the Al-Aqsa mosque (Dome of the Rock) at prayer times; Christian pilgrims kneeling at the stone on which Jesus was anointed inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or Jewish supplicants wailing at the Western Wall.

3. Sunset from the Austrian Hospice

The Austrian Hospice is a Christian guesthouse, situated in the middle of the Muslim quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem. It was built in 1854 for pilgrims by the Archbishop of Vienna, who still owns the institution today.

At sunset, you can witness beautiful views, from its rooftop, of the sun settling down slowly over the limestone buildings of the Holy Land, whilst listening to the call to prayer echoing from different angles – a perfect place to unwind after a long day of sightseeing.

4. Bethlehem: A biblical jewel

Bethlehem is one of the most touristic cities in the West Bank. It’s flooded with Christian pilgrims and non-religious tourists alike who come to visit the birthplace of Jesus.

The city is dominated by a unique limestone architecture, traditional souks and a relaxed atmosphere. The heart of the city, Manger Square, is filled with tourist groups and local by-passers admiring the surrounding religious sites such as Church of the Nativity, Milk Grotto and Omar Ibn al-Khattab Mosque.

The old part of the city is filled with bazaars, eateries and food markets where visitors can admire colourful artisan work and watch the daily life of Palestinians.

5. The Wall of Separation: A first-hand look at the struggle of the Palestinians

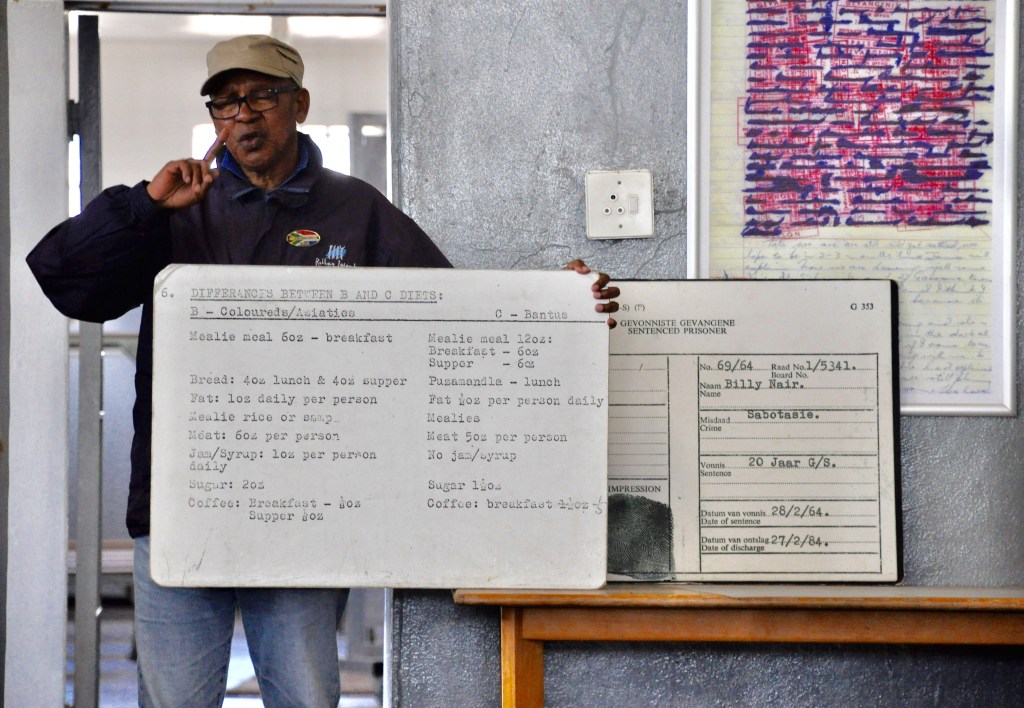

The Wall of Separation is a living reality of the Palestinian struggle, and depending on which side of the wall you stand, you will hear a different story- a wall of apartheid versus a security barrier.

To the Palestinians, it’s a wall of apartheid and occupation that affected many families economically and emotionally when they lost their lands. To the Israelis, it’s a security barrier. The reality is that it’s a giant and ugly concrete wall twisting like a serpentine separating the West Bank from the rest of the country.

Opposite the Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem, the wall has been turned into a canvas for artists and non-artists alike to express their hope for a resolution, dismay of what is happening and feelings of oppression.

6. Ramallah: A cosmopolitan city inside a turmoiled region

Ramallah is the administrative capital and the most vibrant city of the West Bank. The street leading to the crowded Manara Square – with its iconic four-lion statues – is filled with nice smells of freshly baked bread and coffee waft coming from shops.

It’s home to the Yasser Arafat museum and mausoleum, which is an inspiring place to look at over 100 years of Palestinian history and to get an insight into the life of the late Palestinian president.

Mahmoud Darwish is another museum to visit, on the hilltop of Al Masyoun. It was built in tribute to the famous Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

7. Nablus: The little Damascus of Palestine

The city of Kunafeh, olive oil and soap factories is nestled in a valley between Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal. Its old city is a labyrinth of narrow Ottoman-style alleyways filled with colourful vegetable stalls, spices and coffee shops.

Visitors can also go to Mount Ebal for beautiful views over the city, and Mount Gerizim to get an insight into the culture and history of the Samaritan community – one of the oldest and smallest religious communities in the world and which consider Mount Gerizim as a sacred place.

Nablus is also home to Jacob’s Well, which is believed to be constructed by prophet Jacob. Today, it’s found inside a Greek-Orthodox Church with a quiet lush garden. According to Christian tradition, it’s the place where a Samaritan woman gave Jesus a jug of water.

8. El-Khalil (Hebron): Home to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi and a living example of Israeli settlements inside the West Bank

El-Khalil (Hebron) is an interesting city to visit not only because it’s home to al-Haram al-Ibrahimi, but it’s also the place where the impact of illegal settlements can be seen in the heart of its centre.

The alleyways of its old city are covered with metal nets and plastic sheets to protect shop owners and by-passers from the garbage and stones thrown at them by the settlers, who occupy the houses above the shops.

The old city feels like a ghost town, as most shops are now closed. The ones that remain open are; however, a delight to shop from and look at beautiful embroidered materials and local artisanal products.

Al-Haram al-Ibrahimi is the key site in El-Khalil. It’s believed to be the resting place of prophet Abraham and his family, hence its great significance to all three Abrahamic religions and the reason for the tensions inside this city. It’s split into two parts with a wooden door and a bullet-proof window; one part for Muslims and the other for Jewish people.

9. Culinary richness of Palestine

Palestinians take pride in their gastronomic landscape and consider it part of their identity and heritage. A Palestinian culinary experience is an attraction that you can indulge in small eateries or fine dining restaurants. The dishes vary in style from Mezzas, to meaty mains like Maklouba and delicious deserts like Kunafeh.

10. Hospitality of the Palestinians

The Palestinian hospitality is famous in the Arab world and it’s very real. As a visitor, you will be flooded with warmth and invites for coffee or tea, which sometimes gets extended to dinner invitations. Don’t be surprised or alarmed by these gestures – hospitality has been a trait of the Palestinians for generations. Nowadays, it’s a way for them to tell their story over a drink or a meal.